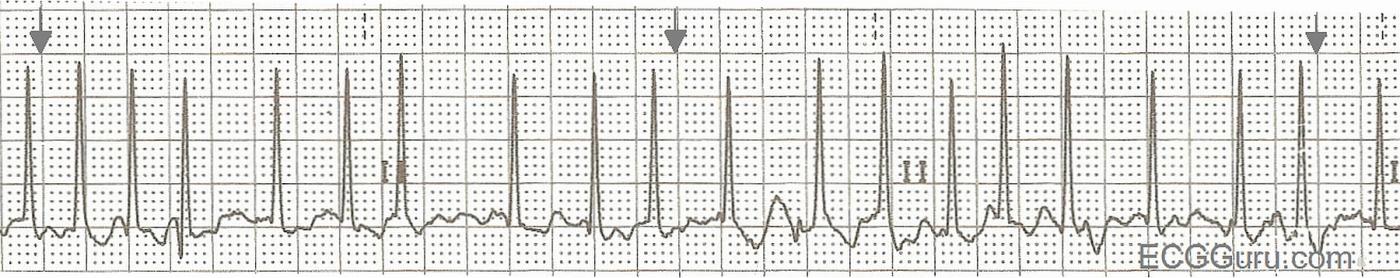

This is a good basic rhythm strip example of atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response showing the identifying characteristics of atrial fibrillation: no P waves, an irregularly-irregular rhythm, and a "fibrillatory" baseline. The wavy baseline will not be seen in all leads in all patients, so it is best to use the first two findings as diagnostic criteria. Atrial fib often appears initially as a rapid rhythm, as the AV node is being bombarded by many impulses from multiple foci (pacemakers) in the atria. Depending upon the AV node's ability to transmit these impulses,however, we could see a slow, normal, or rapid ventricular response.

Atrial fib has very chaotic depolarization of the atrial muscle, resulting in quivering and ineffective pumping of the atria. This loss of "atrial kick" can severely reduce ventricular filling, and can reduce cardiac output by as much as 25%. In patients with a very rapid rate, cardiac output can be further reduced, causing CHF. In addition, the fibrillating atria can form blood clots due to sluggish movement of blood. These clots can embolize and cause stroke. For these reasons, patients with atrial fib are anticoagulated and sometimes the atrial fib is stopped by medical, surgical, or electrical therapy. Recurrence of atrial fib is common after treatment, and for some patients, control of the ventricular rate and anticoagulation become the preferred treatment.

All our content is FREE & COPYRIGHT FREE for non-commercial use

Please be courteous and leave any watermark or author attribution on content you reproduce.

Comments

Basic ECG Strips: Atrial Fibrillation with Rapid Response

Even when the interpreter KNOWS the specific rhythm in question - it is best to approach each arrhythmia by: i) Assessing whether the patient is hemodynamicallly stable enough to allow you the luxury of time to fully assess the rhythm; and ii) Systematic description of what you see along the way toward specifying your diagnosis.

Ken Grauer, MD www.kg-ekgpress.com [email protected]

In fact there is evidence

In fact there is evidence that patients who are reverted back to sinus rhythm either chemically or electrically are more likely to have a stroke due to discontinuation of anticoagulation. Cardioversion is more nessecary for symptomatic relief or in the very early stages of developping a.fib which makes it more liklely to sustain sinus rhythm.

Dr Stasinos Theodorou

MB ChB, MRCP(UK)Interventional Cardiologist

www.cardiolimassol.com

AFib is Often "Silent" ...

GREAT point by Dr. Theodorou! The AFFIRM Trial showed in effect that it didn't matter re longterm risk of stroke whether patients were converted to sinus rhythm or remained in AFib - as the underlying risk of stroke was similar in both groups. Several potential reasons might explain why:

As implied by Dr. Theodorou - the hope is that IF you address AFib when it first presents (before anatomic and physiologic changes have become established in the atria) - that you have the best chance of restoring AND maintaining sinus rhythm (and perhaps also of minimizing longterm risk of stroke).

Ken Grauer, MD www.kg-ekgpress.com [email protected]