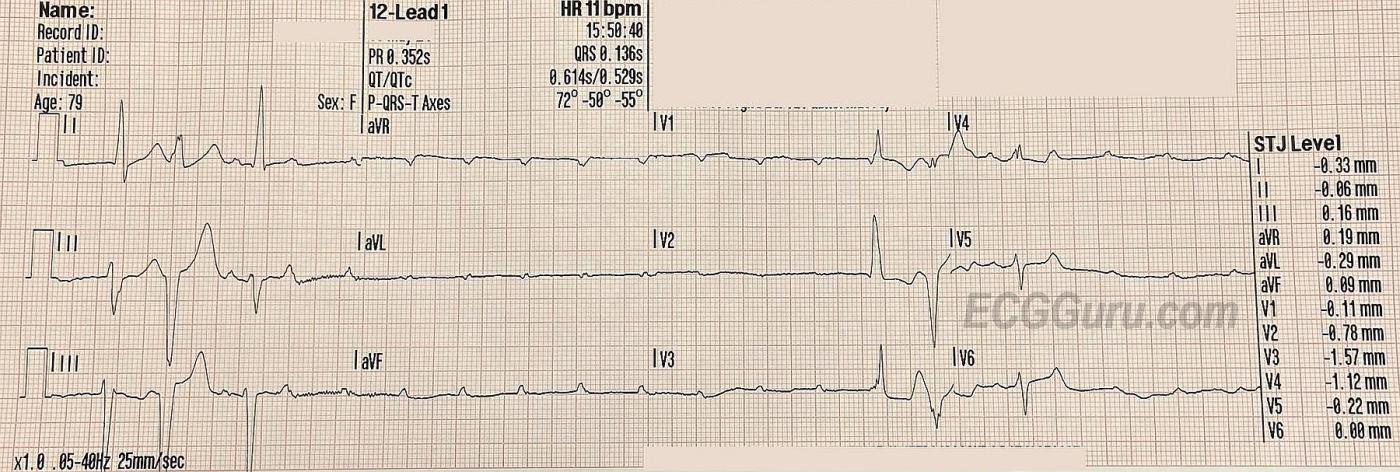

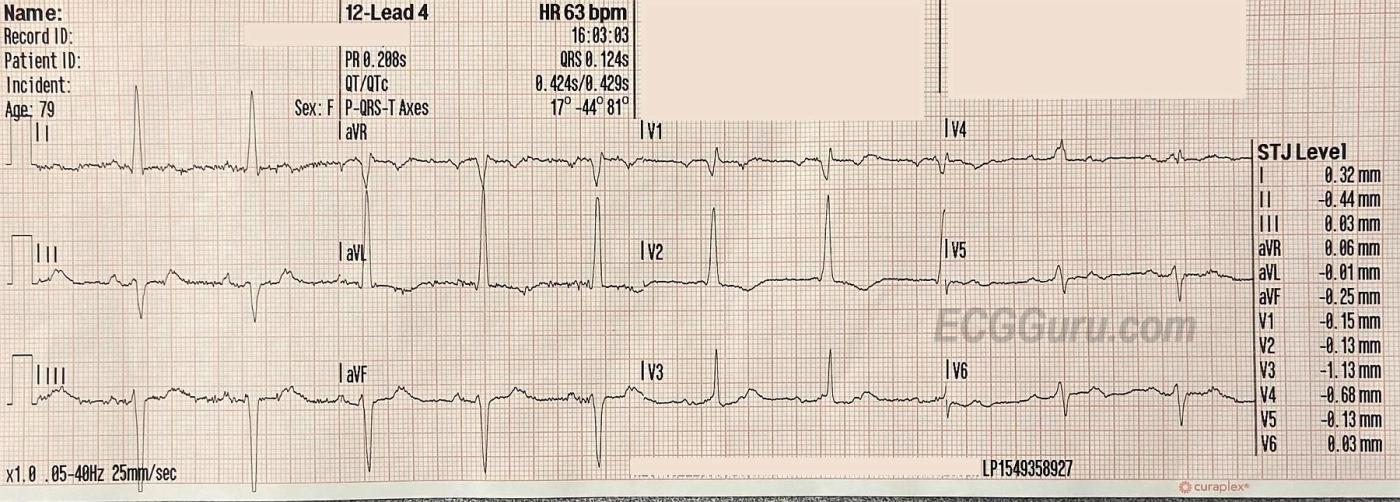

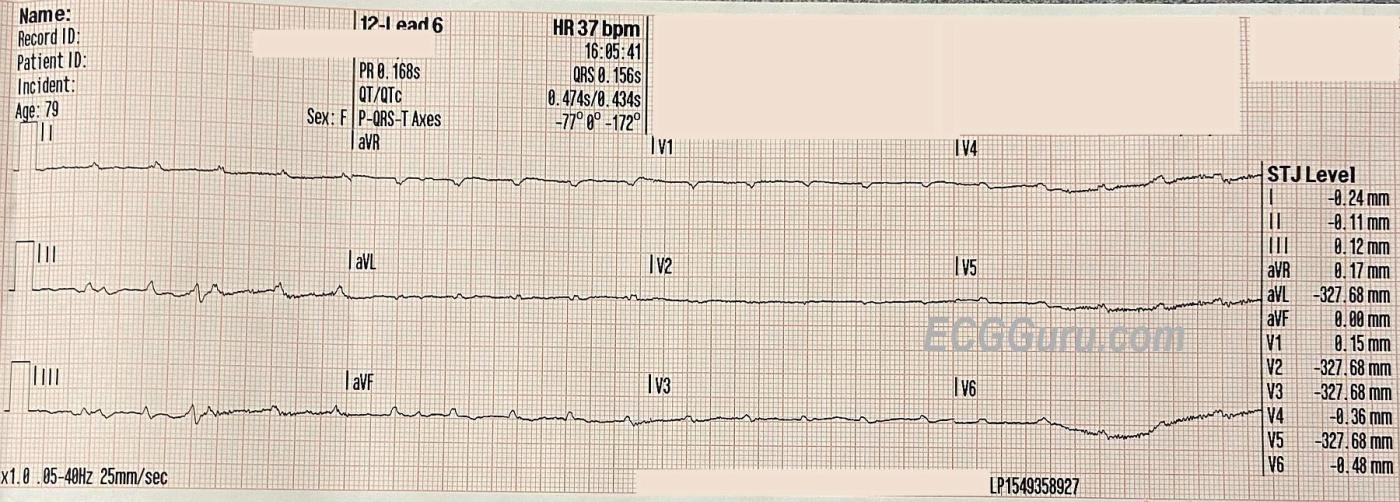

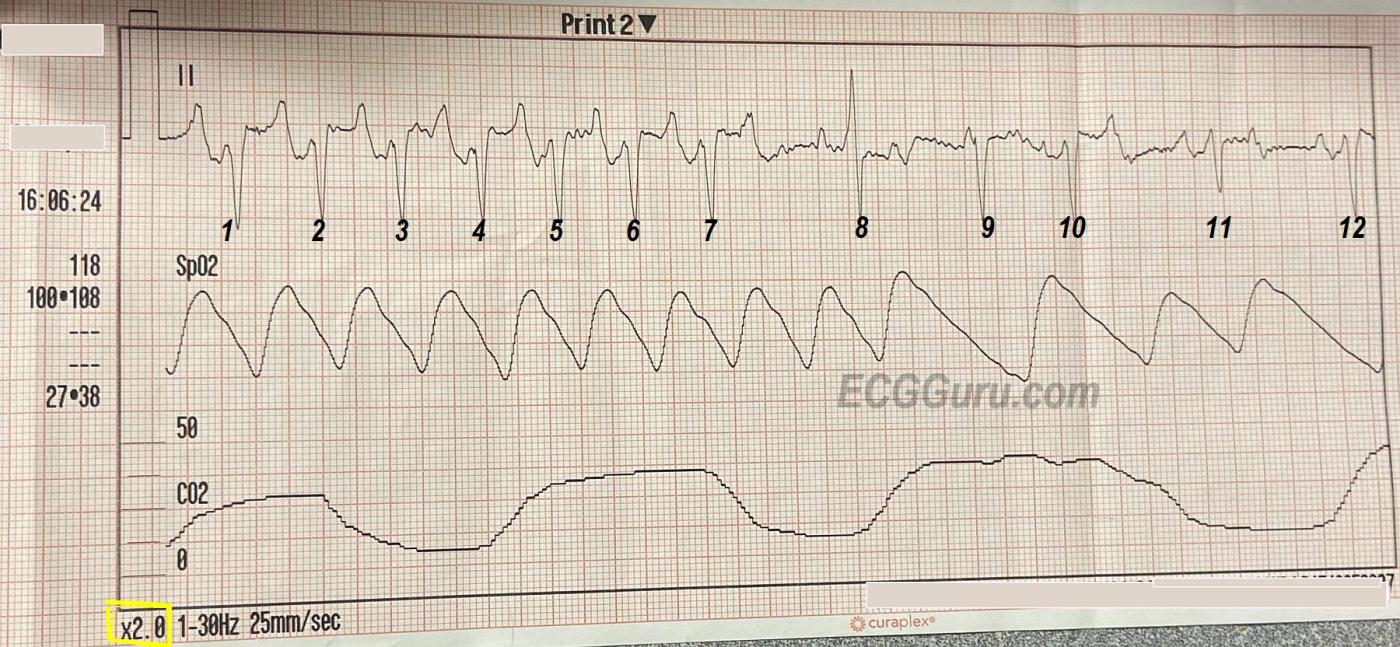

The Patient: This 72-year-old woman called EMS because of a sudden onset of breathlessness and anxiety. She had a history of COPD (asthma), CHF, and Type II diabetes. We do not know her medications or any other history. She was found to have bilateral breath sounds with "minimal" expiratory wheezing. She was alert and very anxious. Her initial pulse rate was recorded at around 60 bpm and irregular. A systolic BP was heard at 140 mm Hg, but the paramedic could not hear a pulse after that. She was given oxygen via CPAP (Continuous positive airway pressure). The first ECG at 15:50 was recorded during this assessment. After appearing to improve, she became neurologically altered, and her level of consciousness varied during the call. She was turned over to emergency department staff conscious and able to speak, but had a cardiac arrest subsequently. The paramedics were unable to obtain followup information regarding the outcome. ECG at 1550: The first QRS on the recording has no associated P wave, and is presumed to be an escape beat, probably junctional, with an interventricular conduction delay (QRS .12 sec.). This is a right bundle branch block pattern with left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block). The second QRS is about the same width, but with a different morphology and discordant T waves, so probably ventricular. The third QRS is very much like the first, except that it appears to be conducted from the preceding P wave. For the next five seconds, there are only P waves, which are regular at about 130 bpm. The three-beat pattern seen at the beginning repeats itself near the end. This ECG shows evidence of severe conduction blocks. The wide QRS complexes indicate interventricular blocks. In this case, some are probably premature ventricular contractions and some are sinus beats with bifascicular block. Even more worrisome is the intermittent loss of AV conduction. This can be called "intermittent trifascicular block", or "intermittent ventricular standstill". This is not a "third-degree AV block", because there are signs of AV conduction, but it is very close. With two of the three main fasicles of the left bundle branch blocked initially, it only takes a block in the remaining fascicle to produce a complete lack of AV conduction. Of course, there are no pulses during the time of ventricular standstill. The really concerning part of this situation is the lack of an ESCAPE RHYTHM. This is a good time for a temporary pacemaker, either transcutaneous or, if available, transvenous. ECG at 1603: This ECG was obtained enroute to the hospital. The patient is once again alert and anxious. There is some artifact which hampers evaluation, but there are two P waves for every QRS complex. The atrial rate is about 120 bpm and the ventricular rate is about 60 bpm. The non-conducted P waves are buried in the T waves of the preceding beats. There is a right bundle branch block pattern with left anterior fascicular block, as we saw in the first ECG. ECG at 1605: Now, the patient has become unresponsive to voice. We see nothing but P waves for the entire ten-second strip. RHYTHM STRIP at 1606: Now there is a tachycardia with the same pattern of RBBB and LAFB. The rate is a bit over 120 bpm. It is difficult to determine the P-QRS relationship because of the artifact. There is one beat with a different QRS morphology (8) that comes in after an interruption of the tachycardia. It appears to be conducted from a P wave, but it is followed by two non-conducted P waves and an escape beat(9). The SpO2 graph indicates a pulse between 7 and 8.The patient felt better and was able to talk with the emergency department physician. The patient suffered a cardiac arrest subsequent to this strip, and we do not know the outcome.

All our content is FREE & COPYRIGHT FREE for non-commercial use

Please be courteous and leave any watermark or author attribution on content you reproduce.

Comments

Masquerading BBB into Ventricular Standstill

Today’s case by Dawn is instructional. The patient suffered cardiac arrest. We unfortunately do not know the treatment interventions en route to the hospital, nor do we know the ultimate outcome. That said — soul-searching retrospective analysis can be insightful.

I’ll add to Dawn’s excellent commentary with a few additional thoughts.

The term, “trifascicular block” is a misleading one that is no longer recommended (Surawicz et al — JACC: 53(11):976-981, 2009 — https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.013). Asystole is a “complete” trifascicular block. An “incomplete” trifascicular block could be any combination of a bifascicular block plus first-degree block — or — that might not be a “trifascicular” block at all, if the reason for the prolonged PR interval is disease in the AV node and not in the remaining fascicle.

Instead of “trifascicular block” — intermittent ventricular standstill (as mentioned by Dawn) is a much more accurate descriptive term. To emphasize — despite minimal conduction, there ARE 2 sinus-conducted beats in the initial 15:50 tracing — so this is intermittent ventricular standstill and NOT complete AV block (as any sinus conduction at all negates the definition of “complete” AV block).

It could be easy to overlook the 2:1 AV block in the 2nd (16:03) tracing — because (as Dawn mentions) — the 2nd P wave is hidden within the preceding T wave. The KEY is to look at all 12 leads on the ECG — with the 2:1 AV block being easiest to recognize by the equally spaced 2 negative deflections in lead V1. And, if we measure the P-P interval in the initial 15:50 tracing — it is IDENTICAL to the distance between those 2 negative P wave deflections within each R-R interval in the 2nd (1603) tracing.

The other important finding to recognize in the 2nd (16:03) tracing is MBBB ( = Masquerading Bundle Branch Block). MBBB is identified by the presence of QRS widening in the presence of at least some sinus conduction, in which QRS morphology is consistent with RBBB conduction in the chest leads — but LBBB conduction in the limb leads (especially when there is a marked leftward axis). The clinical significance of MBBB — is that it identifies a group of patients with very severe underlying heart disease — who have a much higher predisposition for developing severe heart block (needing a pacemaker) — and who have an extremely poor long-term prognosis (See my ECG Blog #419 — for more on MBBB — https://tinyurl.com/KG-Blog-419).

The reason I highlight the diagnosis of MBBB — is that if this patient during sinus rhythm (when last seen by her clinician) had this same MBBB morphology — it may have served as a warning to carefully assess the patient for potential need of prophylactic pacing.

Ken Grauer, MD www.kg-ekgpress.com [email protected]

A Great ECG! A Rare Occurrence!

Dawn...

This ECG is an example of a pause dependent paroxysmal AV block. Looking at the first (top) ECG, QRS #1 is apparently a junctional beat - relatively narrow and well-formed with no P wave preceding it at a conductible interval. QRS #2 is an aberrantly-conducted beat, either caused by a PAC or a PJC. I don't think we can be sure which it is. Those T waves in Leads II, III and aVF are NOT repolarization abnormalities but exactly what you would expect to see with an anterior fascicular conduction delay or block. It is this anterior fascicular block with its strong, terminal leftward force that has resulted in the loss of the slurred S wave in Lead I leading to the appearance of LBBB in Lead I and RBBB in Lead V1 (the "masquerading" bundle branch block mentioned by Ken). If you aren't familiar with this concept, the "masquerade" is in Lead I - it really IS a RBBB.

Now let's focus on the onset of the paroxysmal AV block. One could interpret this as beginning with an atrial pause but it could also be interpreted as NOT having a pause - see my thoughts at the end of this post.

Assuming this block is initiated by a pause (i.e., pause-dependent), here's what to notice: a P wave precedes QRS #3 at a conductible interval. And QRS #3 is the last QRS seen for quite a while! Notice that the P-P interval from the P wave before QRS #3 and the next, non-conducted P wave is quite long compared to the P-P intervals during the block. In my copy of the first ECG, this pause is indicated by the long arrow. This occurs only in very diseased His-Purkinje systems. The pause allows abnormal conducting fibers to depolarize further than they would under normal circumstances. They aren't producing action potentials, but they are depolarizing the conducting pathways probably beyond -60 mV, i.e., beyond the fibers' capability of conducting an action potential. Each supraventricular impulse that reaches the diseased area just adds to the depolarization and the block continues.

Let me be clear: the atrial pause that initiates the block is NOT due to His-Purkinje system disease. It's what is happening in the His-Purkinje system DURING that pause that results in the AV block.

So, how does it end? In most cases - and surely in THIS case - the block is antegrade only. An ectopic impulse that arises BELOW the level of the block is able to invade the area and reset all the cells, allowing antegrade conduction to resume. And that is what has happened here. Two ectopic QRS complexes appear at the end of the ECG. Following the second QRS, a sinus P wave appears to conduct at a conductible interval. But look what happens then - there is a long atrial pause and the process starts all over again! You may ask why the first of the two ectopic beats didn't reset the cells in the diseased area. Well... maybe it did! But the second ectopic beat appeared so quickly that there was no time for a sinus capture.

Please note that the ectopic beats that are able to terminate the paroxysmal AV block must come from BELOW! A PAC can't help.

ALTERNATE ANALYSIS: In looking closely at the first ECG, I see that there could be a P wave (likely P' wave) hidden in the T wave following QRS #3. That would suggest a sinus tachycardia or - more likely - an atrial tachycardia. If that is the case, this would imply an acceleration-dependent paroxysmal AV block (there is no question that this is a PAVB - I'm just considering the cause). The diseased HPS would likely be in the left posterior fascicle because the right bundle and left anterior fascicle have already been eliminated from conducting. This is what Ken was referring to when he mentioned the "dangers of a masquerading bundle branch block." He was absolutely correct! I would also surmise that the block is located in the more proximal fascicle which would allow more Purkinje fiber to develop the ectopy needed to invade the block from below and reset the abnormally depolarized cells.

Either explanation works - it just depends on how we interpret the T wave following QRS #3.

For my 23,000+ followers on LinkedIn, I now post and publish from my own website - https://medicusofhouston.com - which has all the capability I had on LinkedIn. You can contact me via email (from the Contact Us page) or you can message me directly via the chatbot located in the lower right corner of the webpage. (There is no AI used for the chatbot - any response will be from me.) You can also use the chatbot to upload an ECG - just like LinkedIn! I now have three books that are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. I especially want to thank Dawn Altman for her generosity in allowing me to use some of her ECGs in illustrating the books. Dawn wrote the foreword to my first book - "Getting Acquainted With Wide Complex Tachycardias."

Jerry W. Jones MD FACEP FAAEM

https://www.medicusofhouston.com

Twitter: @jwjmd