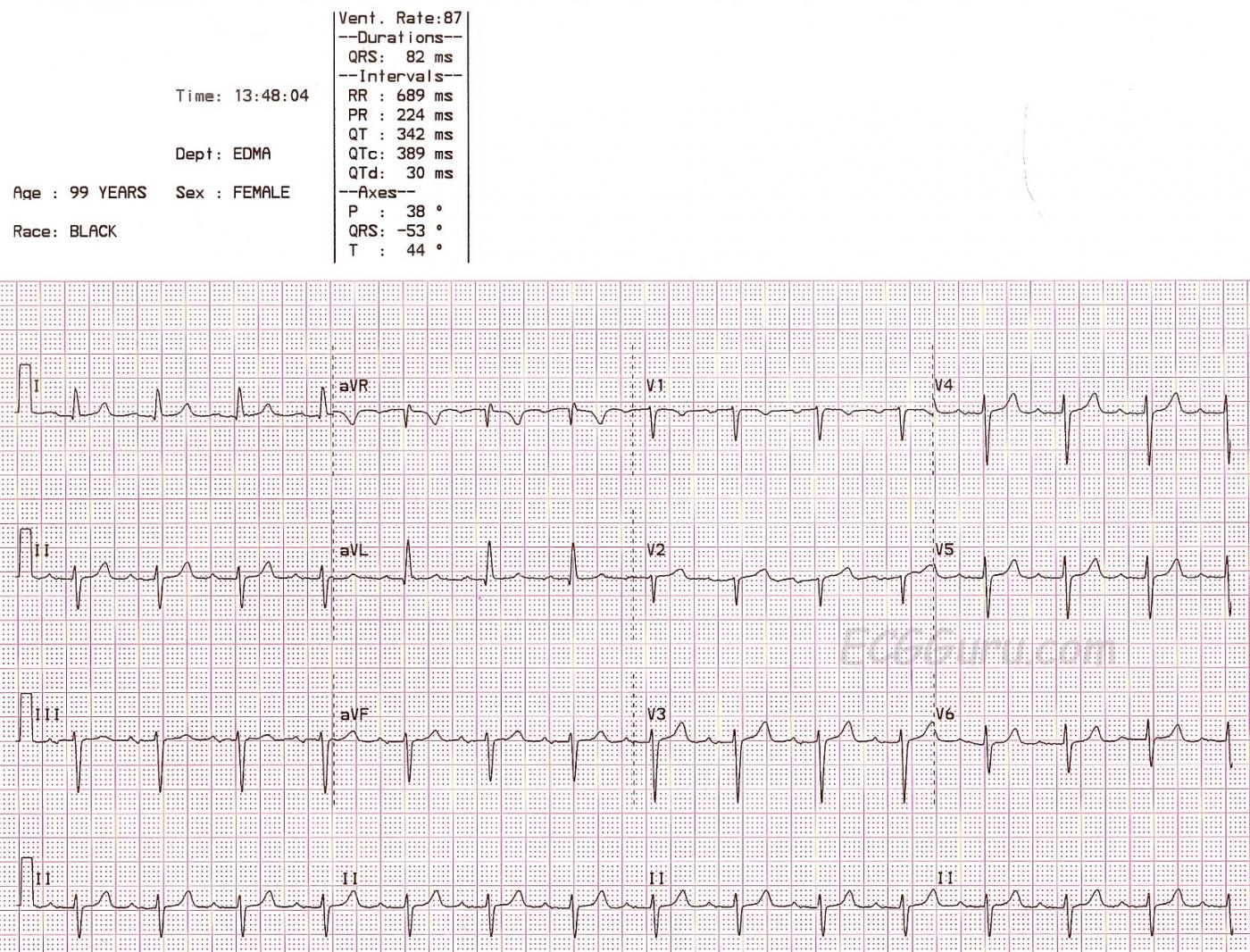

This ECG provides an example of LEFT ANTERIOR FASCICULAR BLOCK (LAFB). It is from an elderly woman for whom we have no other history.

The conduction system below the AV node consists of the Bundle of His, the left bundle branch, and the right bundle branch. While there is some variation among individuals, most of us have two main fascicles, or branches, of the left bundle. The ANTERIOR-SUPERIOR fascicle carries the electrical impulse to the anterior wall of the left ventricle, and the POSTERIOR - INFERIOR fascicle carries the impulse to the inferior area of the left ventricle.

Blocks can occur at any level in the conduction system, including left bundle branch block, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block, left posterior block, and bi-fascicular blocks. LAFB can have many causes, including myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathies, fibrosis of the cartilagenous ring, and aortic valve disease. Left anterior fascicular block is much more common than left posterior fascicular block. Both are also called hemiblocks.

When LAFB is present, the initial septal depolarization forces are still left to right, providing a small initial q wave in Lead I and a small r wave in Lead III. After septal depolarization is complete, the activation vector moves inferiorly and to the right as the electrical wavefront moves through the left posterior hemifascicle and right bundle branch. The impulse finally makes its way to the left and superiorly via slow conduction through myocardium normally depolarized by the left anterior hemifascicle, which is blocked. It is because the terminal left ventricular activation moves upward and toward the left that the inferior leads have negative deflections.

The diagnostic criteria for LAFB are: LEFT AXIS DEVIATION (QRS axis between -45 degrees and -90 degrees); qR pattern in Lead I; rS pattern in Lead III; delayed activation time evident in Lead aVL - the time from onset of the QRS to the peak of the R wave is 45 ms or more. (This example barely makes that criteria); QRS duration normal or slightly wide, but not 120 ms or more (unless there is also RBBB). LAFB also causes poor R wave progression in the precordial leads, with late transition and S wave present in V6.

Before deciding on a diagnosis of LAFB, you must rule out previous or acute INFERIOR WALL M.I. The pathological Q waves that can occur with necrosis can cause a left axis deviation in the frontal plane. The presence of a small r wave in Lead III rules out pathological Q wave in that lead. If any fascicular block (hemiblock or bundle branch block) occurs during the course of an M.I., the patient should be watched carefully for progression of the block. Be prepared to pace if necessary in that situation.

Thanks to our Consulting Expert, Dr. Ken Grauer, for his editing assistance.

All our content is FREE & COPYRIGHT FREE for non-commercial use

Please be courteous and leave any watermark or author attribution on content you reproduce.

Comments

Diagnosis of LAHB can be EASY!

Ken Grauer, MD www.kg-ekgpress.com [email protected]