Dr. Theodorou completed his medical training in 2002 at the University of Leicester medical school, United Kingdom. Following his yearlong pre-registration practice he completed his three year general / internal medicine training which resulted in achieving membership of the Royal College of Physicians of the United Kingdom (MRCP UK). He further specialized as a cardiologist within the West Midlands, completing a period of five years specialist training, in the University Hospital of Birmingham, and University Hospital of Coventry and Warwickshire with a subspecialty in interventional cardiology. After completing the necessary official examinations in Ioanina, Greece, he was accredited with the specialty title in Cardiology and returned to Cyprus in 2011.

Currently, Dr. Stasinos Theodorou is a member of the Cyprus Medical Association, as well as the Cyprus Society of Cardiology. He is also a member of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Intervention (EAPCI), and the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS). During his training he has been academically active and has published several scientific articles in well-respected medical journals. He has also participated in medical research trials through his different posts in UK University Hospitals.

For more from Dr. Theodorou, check his website, Limmasol Cardiology Practice at http://www.cardiolimassol.com and his very interesting FaceBook page, http://www.facebook.com/#!/LimassolCardiologyPractice.

ANSWER:

The job of the emergency cath lab team is very important, stressful and tiring, but above all rewarding. It’s really a great feeling finishing a case with your patient well and smiling, and his/her family being relieved and thankful. The cardiologist and the cath lab team, however, are the last link in a chain of health professionals to actually be involved. In order for the entire system to function productively every single one of these links has to be in place, doing their job precisely and timely.

The patient first of all has to seek attention, let’s say present to casualty. For this to happen there should be some sort of awareness campaign within a community to educate public and warn about the typical symptoms etc. If a patient does not present early it might be catastrophic.

The next link in the chain is the paramedic and / or the casualty staff (if the patient self presents instead of calling 911) This is probably the most crucial step in the patient’s journey into the lab and a lot of the credit for saving a life should be attributed to these amazing people who are constantly on the watch!

As an interventional cardiologist I want to be called out at any time, ON TIME with as little as possible time wasted. From the moment I receive that call I have 90 minutes (preferably 60 according to recent guidelines) to get that artery unblocked and in these cases “time is muscle”. For this exact reason I expect paramedics, nurses, casualty officers or internal medicine physicians to recognize the trigger points on an ECG and MATCH it to the individual patient’s clinical scenario and if appropriate CALL US IMMEDIATELY! Of course there will be false alarms but I would prefer to have those rather than a patient with a MI sitting on a trolley in ED while his/her myocardium dies.

So, when should the cath lab team be alerted?

Starting from the basics one should begin with the patient’s presentation and nature of complaint ( After all the patient is not just an ECG!)

Is the presenting complaint typical of an MI? Is the nature of the pain cardiac, or could it be something else?

Getting it wrong at this stage may result in missing other important diagnoses (Pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pneumothorax etc) and alerting the cath lab will simply waste crucial time until the appropriate treatment is delivered. If the symptoms are atypical reconsider.

An ECG must be obtained within 10 minutes of the first medical contact.

If the symptoms are typically cardiac the following ECG patterns should instantly trigger the team:

1. ST segment elevation measured at the J point in two contiguous leads. Certain specific voltage criteria apply depending on issuing body (AHA/ACC or ESC) but generally speaking anything more than 0.1mV should be considered as suspicious.

2. ST segment depression in leads V1-V3 (> 0.05mV) with positive terminal T-waves or associated with dominant R-waves in V1-V2. This pattern is suggestive of a posterior STEMI and this can be confirmed by obtaining posterior leads (V7-V9).

3. New onset LBBB (If no previous record consider as new, unless proven otherwise)

4. Isolated ST segment elevation in aVR (usually signifies left main coronary occlusion when associated with widespread ST depression in other leads)

ECG patterns that can prevent diagnosis and should be considered highly suspicious if accompanied by typical symptoms of ongoing ischaemia:

1. RBBB shouldn’t hinder the diagnosis of STEMI but patients with MI presenting with RBBB have a poor prognosis.

2. Ventricular paced rhythm. If possible and not time consuming reprogramming the device to evaluate the intrinsic pattern should be considered.

3. Pre-existing LBBB can also impede the diagnosis of an acute MI. Often with acute MI there are marked ST/T changes on top of the underlying LBBB.

Conditions that mimic acute ischaemia on a 12 lead ECG.

These conditions require careful assessment before excluding acute myocardial ischaemia and a cardiology consultation should be requested.

1. Left ventricular aneurysm as a result of an old, full thickness MI. This is associated with Q-waves in the affected territory.

2. Left ventricular hypertrophy. This could be due to primary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, severe aortic stenosis or hypertension.

3. Pericarditis or myopericarditis) usually produces a typical appearance of ST elevation (often called “saddle shaped”) which does not fit to a coronary distribution pattern.

4. Brugada syndrome. This is a genetic disease characterised by an abnormal ECG and predisposes to sudden cardiac death.

5. “Takotsubo” or stress-induced cardiomyopathy causes ST elevation with a specific LV pattern (apical ballooning) with normal coronary arteries.

6. Hyperkalaemia can sometimes cause ST elevation with tall T-waves

7. Sub-arachnoid haemorrhage can cause ECG abnormalities including ST elevation.

8. Pulmonary embolism.

9. Repolarisation abnormalities.

10. ST segment elevation has also been reported in various intra-abdominal conditions, including acute pancreatitis and large hiatus hernia causing cardiac compression.

In the presence of typical symptoms, without any of the above patterns the alarm should not be triggered but that does not mean reassurance. If the initial ECG is normal look for hyper-acute T waves which precede ST elevation.

If there is ischaemia in the form of ST/T changes the patient should be treated accordingly (Antiplateletes, nitrates, low molecular weight heparin +/- Glycoprotein 2b/3a inhibitor) and a 12 lead ECG should be repeated at regular time intervals. If at any given point the ECG shows one of the above trigger patterns, the cath lab team should be called. In these high risk, intermediate cases, continuous 12 lead monitoring is preferable but not always available.

With intractable typical symptoms of ongoing ischaemia the possibility of occluded non-dominant circumflex artery should be considered which sometimes does not result in substantial ECG changes. In this case I personally feel that the decision to take the patient to the lab should be made by a cardiologist.

If the symptoms are very atypical (sharp pain, worse on inspiration, radiation between the scapulae) other diagnoses should be excluded even with a suspicious ECG. A chest X-ray takes less than 10 minutes and can give you a lot of information. At the end of the day I don’t want a patient with tension pneuothorax or dissecting thoracic aneurysm on the cath lab table! (And I did have!!) If the suspicion for aortic disease is high (clinically with the classic signs) a CT scan should be done first.

If there is any diagnostic uncertainty a quick, bedside echocardiogram will often provide the decisive information to guide your next move. It may demonstrate regional wall akinesia consistent with MI or point to a different diagnosis such as aortic dissection or even pericarditis.

When you have covered all the above and you still feel hopeless, not knowing what on earth is wrong with your patient who is in pain with a normal ECG check the following:

1. Amylase. You would be surprised how many times I diagnosed pancreatitis as a cardiologist!!

2. D-dimers. A pulmonary embolism is subtle but deadly and not always easy to diagnose.

3. Surgical opinion if there is any suspicion of gall stones or other upper abdominal pathology (Gastritis, oesophagitis etc)

4. Creatinine Kinase, CKMB, Troponin. It’s never late to diagnose an MI! Your local cardiologist wouldn’t hold you responsible in the absence of ECG changes.

5. Never lose hope!! Do all of the above again if necessary.

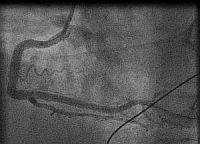

In fact the easiest case scenario for paramedics and casualty (emergency) personnel is a patient with a straightforward, typical, barn door MI for you to simply pick up the emergency phone and call us! We will do the rest starting from getting a diagnostic angiogram, deciding which is the culprit lesion, aspirating the clot, dilating the stenosis and implanting a stent! And yet the most important job of all is that CALL, without which none of the above would ever happen!